Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi or Mahatma Gandhi as he is fondly called the world over, wrote two letters to the German Dictator Adolf Hitler, one in 1939 and the other, in 1940. Both letters were addressed to ‘My friend’. In his book ‘Why I Killed The Mahatma’, Koenraad Elst makes a pertinent observation. He says that for anyone else to call the ‘ultimate monster’ a friend would be considered strange given the circumstances.

According to Elst, Hitler had given rather shocking advice to the British on how to maintain its oppression of the Indian people and also, how to suppress to freedom movement that was, by 1937, in full bloom. In a 1937 meeting with Government envoy Lord Edward Halifax (with whom Gandhi had signed the Irwin pact) Hitler had suggested shooting Gandhi to suppress the Freedom movement. If that did not work, Elst says, he had suggested shooting other leaders of Indian National Congress and then, shoot more freedom fighters if necessary. The plan by Hitler became progressively worse. Elst says that while it would be considered strange to call Hitler a ‘dear friend’, it was patently Gandhian to remain friendly with one’s would-be killer.

The first letter by MK Gandhi to Adolf Hitler was written on 23rd July 1939.

Koenraad Elst says in his book that in his first letter (of the two letters), Gandhi appears to be circumspect in referring the Hitler as his friend when he writes that his friends have been urging him to write to Hitler for the sake of humanity but he has resisted so far as he felt that any letter would be an ‘impertinence’. However, the noted scholar also says that this circumspection on Gandhi’s part was not bourn out of abhorrence for Hitler, but modesty. The last line of his letter where he asks for forgiveness if he erred by writing to him is also considered modesty and scruples by Elst. Elst also says that while this approach of Gandhi is condemned by many, and several believe that it provided Hitler with a carte blanche option, had Gandhi’s method worked, it would have stopped the deportation and genocide of Jews since what happened then was a consequence of wartime.

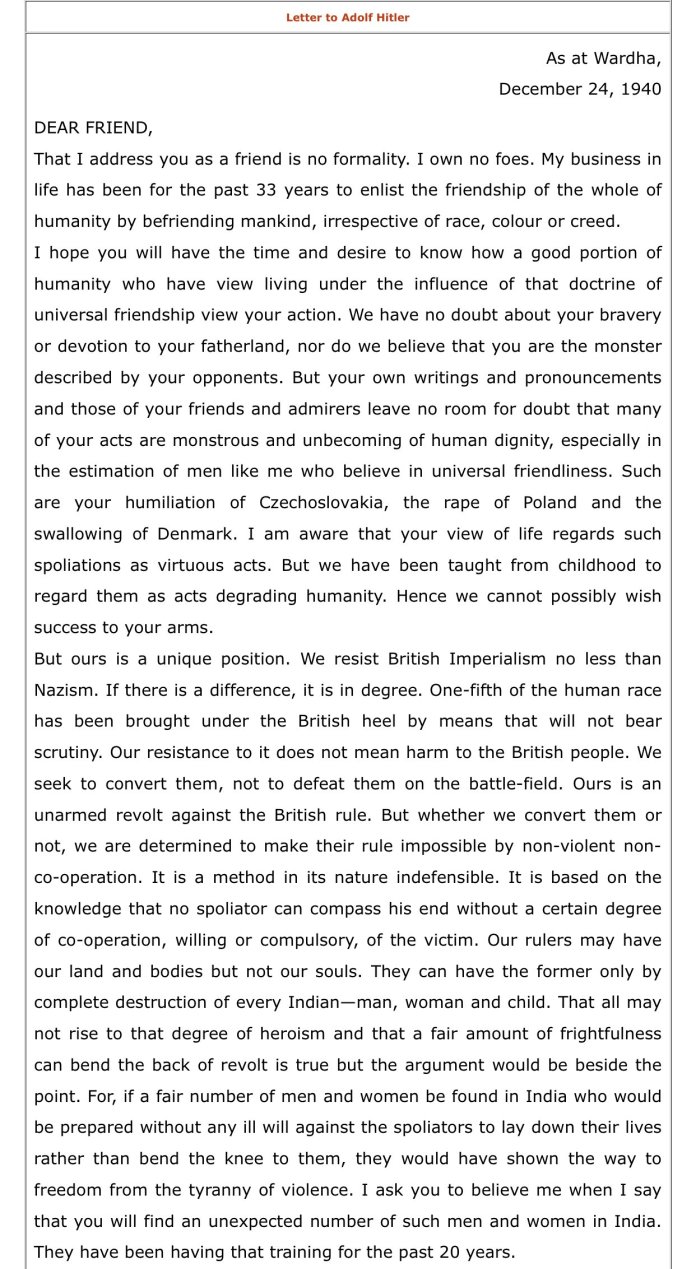

Mahatma Gandhi’s second letter to Hitler came on the Christmas even of 1940. On 24th December 1940, Gandhi wrote a lengthy letter to Hitler. At this time, Germany and Italy controlled most of Europe, the German-Soviet pact was still in place under Churchill and Great Britain was continuing its war against Germany for the invasion of Poland in 1939.

In this letter, Gandhi explains in details his reasons for referring to Hitler as ‘my friend’ and signing both the letters off with ‘Your Sincere Friend’. Gandhi says that the fact that he addresses Hitler as a ‘dear friend’ is no formality because he owns no foes and that his business in 33 years has been to earn the friendship of entire humanity irrespective of caste, colour, creed, religion and race. Gandhi had gone on to call this approach the ‘doctrine of universal friendship’.

It is no surprise that a large part of the criticism that is accrued to Gandhi is regarding his strict tenets of ‘non-violence’ and ‘universal friendship’. Many believe that Gandhi’s adherence to these principles almost bordered on cowardice.

Gandhi vehemently reiterates that he has no doubts on Hitler’s bravery or his commitment to his motherland. He also shuns the popular public opinion that Hitler was a ‘monster’ as described by his opponents. However, he says that some of his acts and writing are monstrous, especially, to someone like Gandhi who considers the principle of universal friendship a way of life.

Talking about the revolt against the British, Gandhi in his letter to Hitler says that the Indian struggle against the British is an unarmed one.

OpIndia had once written:

George Orwell, the great author, once said, “Those who ‘abjure’ violence can do so only because others are committing violence on their behalf.” Gandhi could afford to abstain from violence because there were other great men who had embraced violence for the cause of Indian independence.

The deification of Gandhi has relegated many significant events of the Indian struggle for Independence to historical obscurity. The one event which suffered the most was perhaps the British Indian Royal Navy uprising of 1946. Protests against the poor quality of food and racism by the British which began at HMIS Talwar soon spread to Castle and Fort barracks onshore and 22 other ships and other naval establishments. They demanded the release of political prisoners and the Indian National Army (INA) personnel.

The mutineers had widespread support among the public. They carried aloft a portrait of Netaji Subhash as they took out a procession in Bombay and flew flags of different hues which signalled the unmitigated desire for independence that had gripped the nation. Ultimately, an army battalion had to be inducted to save the situation for the British. After many dead and injured civilians and following assurances of sympathetic treatment by senior leaders of the Congress who were against the mutiny from the very beginning, the mutineers eventually surrendered.

It is thus unfair to say that the Indian struggle against the British was purely an unarmed one, thus, belittling the valour of many other freedom fighters.

Gandhi, however, did not judge Hitler mildly. He did refuse German help in securing freedom from the British and those reasons too are written off in the letter. “We would never wish to end the British rule with German aid”, Gandhi wrote.

Elst in his book supports the method adopted by Gandhi, however, says that Gandhi was wrong in assuming that to disarm the enemy one needs to disarm himself. He writes that while preparing for war is necessary, the target should be bloodless crisis management.