Since the time the Wuhan Coronavirus pandemic began, India has been facing a constant barrage of criticism. Why is India testing so few people? Are India’s stringent testing criteria leaving out too many affected people who are spreading the disease all around the country?

Let us hope at least some of this criticism comes from well meaning concern, although I suspect much of it does not. But without anyone on either side getting defensive about their position, they really do need to explain this.

While these numbers are changing rapidly in real time, these figures are broadly correct. Till now, India has carried out a total of 25,144 tests and detected 693 cases, which comes to 2.7%.

Meanwhile the United States has carried out roughly 370,000 tests and detected around 60,000 infections, which is a rate of 16-17%.

Those two are very different numbers and very far from each other.

The irony here seems to be this: the wider you cast the net, you should have a lower and lower percentage of actual affected persons.

On the other hand, India is testing people who are already showing symptoms, have travelled abroad or have come into direct contact with those having a travel history. For a fairly long time, India was applying even more stringent criteria: only those with travel history (or direct contact with such people) and who are already showing symptoms. In other words, India was testing almost exclusively people in the highest risk category of contracting the Wuhan Coronavirus. This should have pushed the percentage of detected infections higher, not lower.

South Korea has drawn praise all across the world for its efficient and widespread testing after the breakout of the Wuhan Coronavirus. So far, Korea has carried out about 350,000 tests and detected about 9000 cases of the virus, which works out to 2.5%. That is strikingly close to India’s number.

This genuinely could be good news for India, a ray of hope. It does suggest that India might actually be testing at a very appropriate rate. So far, with around 700 infections, that means the disease might not have gone out of control in India. It might really still be stuck in Stage 2 instead of the truly terrifying Stage 3 (community transmission).

There are other considerations here, of course. We know that the number of infections goes up exponentially. The testing ability also goes up with time, but perhaps not as fast. Perhaps therefore the ratio between the number of infections and the number of tests will go up as time passes?

So what if we went back a little into the past and looked at these same countries when they had done fewer tests?

By Feb 29, Korea had done 55000 tests and detected 3000 cases. This works out to 5.7%, which is more than the 2.5% in Korea today. So the ratio went down with time, not up.

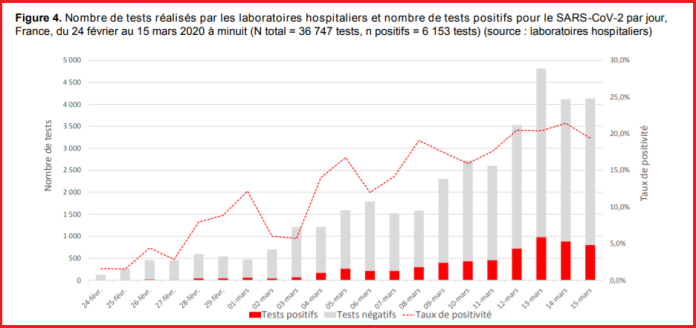

The French Health Agency has some data that is particularly eye opening in this regard.

Till March 15, France had carried out 36747 tests (not far from our current 25000 tests) and discovered 6153 cases. That’s a rate of 17%, a very far cry from our 2.7%. As of now, France has carried out 1 lakh tests and reported about 20,000 cases, which works out to 20%.

There is a very good chance here that India is doing something right. There is no room for complacency here, but definitely grounds for cautious optimism.