For people settled down in one place, or the civilised people as we like to call them, it is necessary to build a home. In fact, the standards of civilisation are often measured, among other things, by the then available scientific planning, longevity of structures built, aesthetic appeal, and successful completion of buildings that range from religious, to the military, to residential structures. So it is not surprising to find Indian writers from ancient times quite taken up with the subject of architecture; and this obsession is evident in all forms of literature varying from the Vedic, to Epics, Puranic, Buddhist, Jain, Agamic, historical, and even the political treatises.

For delving into the depths of ancient Indian city architecture, a glance at the pre, proto, and historic era city/town planning in India (approximately 5500 BCE to the start of the Common Era) will give a good view of how things looked back then.

Looking at the Harappan advanced form of city planning from various excavation sites (photos from the ASI archives in public domain)

The remains include parts of fortifications, well-planned drainage system, houses with many rooms and sometimes double-storeyed, separate bathroom and toilets, and an advanced system of interconnected tanks and reservoirs for elaborate water management.

Interestingly from different site excavations, it has been revealed that it was quite likely that many Harappan cities (Mohen-jo-daro, Kalibangan) had a twin mound system (as seen in the 3D reconstruction image above), wherein a raised fort or citadel would lie on the west and the lower town would be in the east. In some cities (such as Lothal) there were no raised mounds for a citadel, and the citadel was separated from the town just by a brick wall. Dholavira, on the other hand, had a middle town between the citadel and lower town.

There are suggestions that the citadel could have been the place for the rich and the powerful (as this part always had the famous buildings such as great bath, granary, house of priests, etc), while the lower town could have been for the common citizens (public buildings, houses, blocks and streets with lanes and bylanes). The citadels and the lower towns were both surrounded by high walls with broad mud foundations having gates and moats. The fortification walls generally were parallelogram in shape with huge towers.

Most cities of the Harappan sites show neat blocks divided by broad roads running at right angles. Inside the blocks are seen narrow lanes with houses crowding around them. Roads have been found to have been paved with mud bricks with a layer of gravel on the bricks (Lothal). Often the corners houses were fenced off to avoid damages or sometimes rounded off for the same reason.

A major hallmark of the Harrapan civilisation was the advanced and well-planned drainage system in place, which is unparalleled in any of the contemporary civilisations. Main street drains were covered with bricks and stones, and there were tertiary drains that connected each house to the main drains. Second storeys had drains built inside walls that ended just above the street drains.

There were man-holes and soak pits with covers for removing solid waste. The entire thing then emptied itself into brick culverts to be finally led to the fields outside city limits. Thus, we see an intricate system of intersecting house drainage pipes, public drains, and arterial drains.

Harappan era houses were of different sizes; had many rooms for different purposes; a courtyard; were sometimes double storeyed with staircases leading to the second floor; the floors were either tiled, or plastered, or covered with clay and sand. Bricks used in construction were of uniform ratio and size.

The Harappans had provisions for a separate bathroom and toilet in each house. Sometimes a group of houses would have a separate common bathroom. Bathrooms had bathing platforms with sloping floors to drain off the water into the drain.

Toilets in Harappan sites would generally be a hole over a cesspit. However, in elaborate styles, a commode-like system would be made out of a big pot that was fixed to the ground. The pot would then have a hole at its base from which the waste would flow out. Sometimes the pot would be connected to a drain via a sloping channel.

Harappan sites show an elaborate system of water management for collection and distribution of potable and bathing water. There were separate channels for freshwaters, rainwater collection, and wastewater drainage. They also had systems for collecting/harvesting rain waters as evident from the numerous reservoirs, cisterns, and wells.

The Ancient Indian Architectural texts

In the Indian context, the term architecture is included within the realms of Silpasastra; a treatise, which thankfully has survived the ravages of time and tyrannical vandalism. The term Silpasastras, which when literally translated, means the study of fine or mechanical arts, and there are 64 such arts that can be studied. Indian architecture, known as Vastu Sastra, is seen as a part of a subdivision of the Silpasastras, as it encompasses much more than what the term ‘architecture’ generally implies.

Thus, Vastu-sastra would include, besides the basic architecture, all kinds of buildings being built (civil and military engineering); it would also cover laying of parks and gardens; town planning; marketplace designing; digging drains, sewers, wells, and tanks; building dams, bathing ghats, walls and embankments.

Furthermore, it would also be a part of designing furniture suitable for the houses built. Besides these, Vastu Sastra also includes designing of clothing and accessories, such as headgear and various ornaments. Carving of sculptures of deities and famous people are also a part of Vastu Sastra. Even basics, such as selecting a site, testing the soil of the site, and ascertaining the cardinal directions of the site are all part of this ancient science of architecture better known as Vastu Sastra. The treatise that brings together all the varied topics under Vastu Sastra is compiled into 70 chapters and titled as Manasare-vastu-sastra.

Vastu Vidya or Vastu Sastra is so comprehensive and broad in its discourses that it is almost co-extensive with the Silpasastras. As Manasara explains ” Vastu is where the gods and men reside (Sanskrit word vas = reside/sit).” This would include ground or dhara (the principle object as nothing can be built without it), buildings or harmya, conveyance or yana, and an object to rest like a couch or a bed or a paryanka. Town or city planning would primarily involve the planned use of ground and buildings.

Architecture in Vedic Literature

While the concept of town or city planning is undoubtedly a very ancient branch of Indian science, the technical details of building structures appear for the first time in the treatises that deal solely with architecture (Vastu-sastras), and are absent in the non-architectural literature prior to the Vastu-sastras. While there is little about the structural details of a house in the Vedic literature, the early Vedas do carry casual references to this art. That people of this time did not live in caves and had proper houses as their residences are clearly evident from the various synonyms used for a house, and also in the naming of the various parts of a house such as doors, crossbeams, and pillars (Rig Veda I, 13-39).

While details are sketchy, the hymns of the Atharva Veda do give information on the simple house construction, where it is said four upamit (pillars) were set up on a chosen site, and beams were laid angular as props (pratimit), while the pillars were supported with cross beams (parimit). The roofs were made of rib-like structures constructed of bamboos, walls had palada (grass bundles) and the entire structure was held together by bindings of various types (samdamsa, nahana, etc).

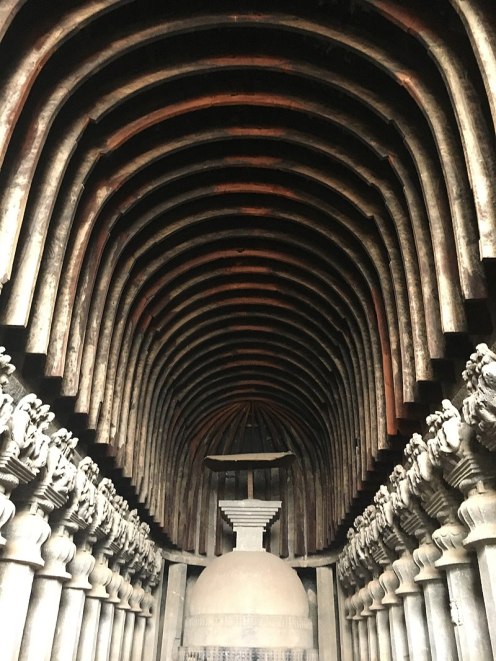

These houses had many rooms and it could be securely locked up (Rig Veda VII, 85, 6). A closer look would show that these houses bear similarities to the house of the Todas, and had a similar wagon headed roof in all probability. The Vedic descriptions also bear a striking similarity to the rock cut chaityas and assembly halls of the Buddhist caves in western India, wherein some of the oldest ones the wooden ribs on the vaulted roofs still remain (Fergusson, History of Indian architecture).

There are also stories in the Vedas of Vashistha wanting to live in a three-storeyed house; an able king “who sits in a substantial and elegant hall with thousand pillars;” and there are mentions of large mansions of wealthy people that had many pillars and doors (Rig Veda I, II, IV). Varuna and Mitra are shown to be living in splendid palaces. From these writings, it is pretty evident that while these descriptive verses tend to exaggerate in an attempt to glorify the deities, but they are certainly based on real buildings that the writers had seen (Muir. 1868).

Furthermore, R L Mitra in his Indo- Aryans opines that while mentions of pillars, doors, and windows may or may not be decisive indicators of masonry buildings, but bricks would not have originated unless they were to be used for specific reasons, and it would be absurd to suppose that bricks were invented but never used for building houses. In this context, if we read the Sulva sutras (supplement to Kalpa sutras), we find that while discussing the details of the vedis or fire-altars, it is mentioned that these altars were made of bricks. These altars for Soma sacrifices were made based on specific principles and precise measurements, and were likely the foundations of religious architecture in India.

The fire altars, first mentioned in the Taittiriya Samhita, had different shapes and were constructed of 5 layers of bricks (sometimes even going up to 10-15 layers too), while each layer had 200 bricks. Precise measurements were given as to the sizes and area to be covered and that were to be followed carefully while constructing these fire-altars.

The Vedic literature also frequently mentions villages (Grama), and towns (Pur), of which the Pur is frequently mentioned in the Rig Veda. The Pur also referred to forts and finds frequent mentions with varied names, such as urvvi (wide), prithvi (broad), a stone built fort (asmamayi), of iron built ones (ayasi- though this is more likely to be metaphorical in nature), a fort full of cattle (gomati) denoting that forts were used as strongholds to keep cows, forts used during autumn (saradi– referring to being occupied by the dasyus), and forts having 100 walls or satabhuji.

Instead of being permanently occupied like the medieval forts, these forts could have been used as places of refuge during times of need. Some historians (Pischel and Geldner) opine that these fortifications could be of the Pataliputra type as mentioned by Megasthenes.

Thus, apart from the well developed urban centres in the Harappan sites, and the frequent Vedic references to forts and towns, it is for certain that flourishing cities/townships existed much prior to the start of the Common Era. Megasthenes mentions that the grand city of Pataliputra was more than 9 miles in length. As we learn from details of cities given in various texts and early reliefs (discussed further below), Mauryan era cities like Pataliputra were not any sudden developments, but a continuation of an already established and known urban culture (Coomarasway).

From the Vedic texts, it is quite clear that the writers of these verses were well aware of fortifications, villages, towns, forts, carved stones, stone-built houses, and brick structures. The basics of architecture were already in, which were handed over from generation to generation most likely through oral traditions of memorizing knowledge and facts.

The varna-guild form of social structure saved the knowledge from going extinct, and it was only much later that these were compiled into treatises for the better preservation of traditional knowledge. This is evident from the fact that while the extant Silpasastras are placed at around 5th c. CE, we find from different accounts the presence of an advanced and well developed Pataliputra city in the 3rd c. BCE. Since such large cities cannot be built with a sudden overnight knowledge, it can be safely said that the knowledge and science of architecture were already well present by then; however, compilation in form of books/treatises happened at a later period.

Architecture in Buddhist texts, the Epics, and the Puranas

In Buddhist literature (Mahavagga, Chullavagga, Vinaya texts, Dhammapada Atthakatha, MilindaPañha, etc) there are plenty of references to high walls, ramparts and buttresses, gates, watchtowers and moats alluding to the fortification of towns and cities. Mentions are made of houses opening directly to the streets, thus hinting at a lack of enclosed spaces like gardens in front. These mostly talk of a large group of houses clumped together around narrow lanes, of sacred groves, and vast expanses of rice fields beyond. The Jataka talks of individual houses that remain separate from villages and towns.

In some places, Buddha is found sermonizing on architecture, and in one instance he tells his disciples, ” I allow you O bhikkhus, abodes of five kinds: Vihara (monasteries), Arddhayoga (special Bengal buildings that served both religious and residential purposes), Prasada (storeyed residential houses), Harmya (storeyed mansions or palatial homes), and Guha (small houses)” (ref: Vinaya texts, Mahavagga).

There are detailed descriptions of arama griha (rest houses) for people who liked to lead a quiet life and stay a little away from the hustle-bustle of the towns. As per the books, such houses should be located not too far or too close to the towns, the compounds are to be surrounded by three types of walls (stone, brick, and wooden fencing), and further surrounded by bamboo fences, thorn hedges, and moat-like ditches.

Houses should have living rooms, resting rooms, storerooms, halls for services, halls attached to bathrooms, closet rooms, cloisters, open-faced mandapas, and ponds (Chullavagga, VI). The inner chambers are to be divided into three parts: square halls (Sivika garbha), rectangular halls (Nalika garbha) and dining halls (Harmya garbha). Verandas or alindas were essential for these houses, and were also present in prasada or storeyed houses, which were referred to as a veranda supported on pillars with elephant heads (Chullavagga, VI). Details of doors, windows, stairs, rooms and jaalis on them, and seven storeyed buildings (satta-bhumika-prasada) are frequently found in various Buddhist texts. There is another very interesting structure mentioned in the Vinaya texts.

These are the hot-air baths, which are described in great details; structures similar to the later period Turkish baths. Built on raised platforms, with a facade of stones or bricks, these buildings had stone stairs leading up to a veranda with railings. Roofs and walls were made of wood, with a layer of skin on it, and then a layer plaster over it all. The lower part of the walls was made of bricks. There were antechambers, a hot room, and a bathing pool. Seating arrangements were made in a circle around a fireplace in the hot room, and bathers had water poured over them. Digha Niyaka also speaks of ornamented open-air bathing tanks. Such ancient baths have been found in fairly preserved conditions among the Anuradhapura (Sri Lanka) ruins.

The Epics abound in the descriptions of cities (nagara), large palatial mansions, storeyed buildings, verandas, porches, victory arches, tanks with masonry stairs, prakara or walls, and various other structures which are all indicative of a well developed and flourishing architecture. The city plan of Ayodhya as given in the Ramayana, is found to be similar to the town-plan guidelines as laid down in the Manasara, which included beautiful devayatana (temples), gardens, alms-houses, assembly halls, and mansions.

Ramayana also gives a detailed description of the beautiful city of Lanka in its Lanka-kanda. Mahabharata provides us with short but vivid descriptions of the cities of Mithila, Indraprastha, Dwaraka, among many others. Sabha-parvan provides us with a detailed description of different assembly halls, using examples of Indra sabha, and halls of Varuna, Kubera, Yama, and the Pandavas. In both the epics there are details of lofty buildings (mostly painted in white) and large balconies; windows with lattices; comfortable rooms; king’s palaces; separate mansions for princes, ministers, army officers, and chief priests; smaller houses for common people; assembly halls; courts; and shops.

The Puranas deal with the topic of architecture in a more serious manner than the casual descriptions as found in the epics. All the 19 Puranas have dealt with the subject, however, 9 of them have dealt with the topic in a more systematic manner, which in turn provided material support to the Silpa-sastras compiled later. Matsyapurana has 8 chapters with detailed discussion on architecture and sculptures. Skanda purana has three extensive chapters that discuss the planning of laying of a large city.

Besides these, the other Puranas that extensively talk on architectural science are the GarudaPurana, Agnipurana, NaradaPaurna, VayuPurana, and BhavisyaPurana (a late Purana). Brihat-samhita composed by Varahamihira also devotes 5 chapters to architecture and sculpture and gives the subject a thorough and masterly treatment. From a definition of the science of architecture to choosing sites, soil testing, plan of buildings, to elaborate and comparative measurements of storeys and doors, carvings. etc., all are dealt with great details in this treatise.

Kautilya Artha-sastra has 7 chapters on the science of architecture, with a focus on structural details. Interestingly, this book gives detailed descriptions of forts and fortified cities, palaces with underground tunnels or surang, military and residential buildings within the scope of town planning.

A closer look at the ancient Indian cities

As we look at the various books that deal with architecture in ancient India, we find that the cities were chiefly built by nagara-vardhaka or city planners/architects, who had help from assistants like itthaka-vardhaki (brick layers), and vaddhaki (carpenters). These workers lived in their own community-based gramas or villages (example a grama where only carpenters lived), and came to cities only for their work. As per some records, there were 18 guilds (seni) that controlled the craftsmen, such as, the vardhakis, cittakara (painters), kammara (smiths), etc., that worked as per the norms laid down in their traditional crafts work.

The most important aspects of a city appears to have been the moat or parikha, walls (prakara), gates (gopura), defense towers (dvara attalaka), gatehouses (dwara-kotthaka), king’s palace (raja-nivesana, prasada), temples (devasthana), and monasteries (panna-sala). Besides these were smaller houses (gaha), other mansions (nivesana), granaries (kotthaka), alms houses (dana-sala), markets (antarapana), shops (apana), saloons, taverns, and slaughterhouses. Other essential components of cities were parks, gardens, lakes and ponds, tanks, sacred trees and groves, a central square (singhataka), main streets (maha-patha, raj-magga), ordinary streets (vithi), crossings (catumahapatha), and alleys (patatthi). There were streets occupied by particular varnas, such as a street for traders/ Vaishyas, a common sight in many parts of India until recently. Outside the cities stood the suburbs (nigama) and villages (grama).

The fortified cities that are seen in Sanchi and on other early reliefs are as per the textual definitions that we read in various old treatises that deal with ancient Indian architectural science. These reliefs when studied closely for architectural features will be found to bear similarities with the later period, medieval, and even modern era architectural forms, in the context that many of the ancient characteristic features are found preserved in these later structures.

While the ancient fortified cities have long disappeared, the reliefs remain behind depicting how they once stood tall, and a walk through any of the medieval city gates such as the Gwalior fort, Bijapur fort gate, or the Gujarat and Jaipur city gates will show the how close the architectural connections are between the ancient, the medieval, and the present.

How an ancient Indian city looked: Reconstruction of Kushinagara city gates and the city beyond at 500 BCE, from a Sanchi relief

References:

Photos from the ASI archives in public domain.

Ananda Coomaraswamy, Early Indian architecture.

Binode Behari Dutta, Town Planning in Ancient India.

John Muir, Original Sanskrit texts on the origin and history of the people of India, their religion and institutions.

Prasanna Kumar Acharya, Architecture of Manasara.

The cover photo is a reconstructed image of the Lothal port, from the ASI archives.